I was visiting an old friend on Quadra Island in British Columbia when I began my spiritual search. It was 1970 and I was on summer vacation. There were only eight people in my friend’s community and they all practiced Zen meditation. I learned their practice and participated with them. Just as when I learned Transcendental Mediation a few months before, I felt I was on the right track but hadn’t yet reached my goal. After a month or so there, I met a young man who said to me: “You’re looking for something, and I can’t help you, but I think I know someone who can.” He described to me a friend of his from law school. She had dropped out, hitchhiked across the country, and ended up at a place called Ananda. When he said he’d received a postcard from her that said, “I’m so close now, I can almost touch it,” I felt: I have to meet her. Her words told me that she had been on a similar quest and had found some real answers.

I left the next day and hitchhiked to Ananda from Canada. I had no idea what to expect, knew absolutely nothing about yoga. When I arrived and asked for Shivani, I was told she was “in silence.” She appeared and silently listened as I tried to explain who I was, what I was seeking, and how I came to be there (somewhat awkwardly since I’d never tried to speak to someone “in silence” before). At the end of my speech, she broke her silence and welcomed me like a long lost sister. As she showed me around the Village, she began talking to me about deep aspects of the yogic path, and later taught me some yoga postures. I spent my time at Ananda picking blackberries, working with Shivani in the garden, meeting people, and talking philosophy. I could only stay four days because I needed to return to Berkeley for graduate school. In that short time I became a vegetarian, a hatha yoga lover, and most importantly I had found a place inside myself that I had been seeking.

That Thanksgiving I came back to visit. Ananda was a new and unfamiliar world to me. I remember bringing Shivani a gift of a tiny bag of Calmira figs. This time on my arrival, someone said, “Oh, Shivani is in seclusion, but she just started, and I’m sure she’d want to see you.” Nervously I approached, uncertain about the etiquette involved in this unknown situation. Just as I walked up to her teepee, the door was blown open by the wind, and she emerged to pull it closed. She exclaimed, “Oh, I was wondering how I could find you again!” We spent the afternoon talking about many things, including my uncertainty about whether to drop out of graduate school. Her simple statement, “Don’t worry, it will all become clear to you,” helped me to relax and be open inwardly.

I moved to Ananda on my 24th birthday in 1971 and began helping with the health food candy business Shivani and a couple of other women had started. We would volunteer in the garden in the morning, leaving for work at 7:30 a.m., then return home to our “paying” job in the afternoon. It was many months before we made any money, and the highest salary we ever earned was about $90 a month. I had one of the few cars at Ananda, and my little Volkswagen served as our pickup truck for the business.

One of the dearest people to me in those days was Haanel Cassidy, who started the garden. He was 68 when I arrived at Ananda. At our first meeting, I remember climbing into his pickup truck and seeing a copy of the New Yorker, where he had been a photographer for the Conde Nast magazines. There he was known as “Cassidy, the Waltz King.” He also had a magnificent bass voice and loved to sing Negro spirituals. He was an excellent cook. Everything about him was orderly and sophisticated.

Haanel Cassidy was a striking contrast to the early days of Ananda. We were mostly young people, just out of college, exalting in a sense of freedom from meaningless rules. We were seeking Order on the highest level, but down here on earth things were quite casual. Haanel faced endless frustrations working with us. But we were his friends, and he loved us.

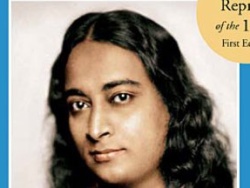

Haanel had become a disciple of Yogananda right after Master died in 1952. He was very loyal to these teachings and to meditation, waking each morning about 2 a.m. to meditate for three hours or so. Swami Kriyananda met him in the late ’60s and invited him to retire at Ananda and just meditate. But Haanel was an extremely serviceful person and felt that a community should have a garden, and it was up to him to start it. He sometimes wondered if he had sacrificed his own spiritual progress to do this. Haanel was also a loyal friend to us all. I’d go to his little cabin and sit down and have a cup of Pero, prepared to perfection. He invited a group of us to meditate with him every Sunday night, just to help our meditations. He also gave lessons in singing, elocution, or calligraphy to anyone who asked him. He could be the grouchiest person or the dearest.

My mother came to visit me after I’d been here about two months. I was then living at the Seclusion Retreat in a decrepit, green armored truck. My mother was in shock her first two days here. At that point there were almost no buildings at Ananda, and no outward signs to indicate any stability. She spent a lot of her time here wondering where she’d gone wrong as a parent. Perhaps I had enjoyed Girl Scouts too much, or perhaps she’d failed to answer my questions in the right way. She plied me with questions about Ananda. Her main fears were about my financial security and my seeming isolation from the world.

On her second day here we went to the Village area so I could work in the garden. While I worked, she wandered off and began talking to some of the Ananda members. She had a long talk with Jaya about his background in anthropology and how he felt about the work he was doing now. She talked with several others as well, and by noon, when I came to find her, she was buoyant. She referred to my armored truck lightheartedly as “The Grasshopper,” and suggested that we paint it. We bought some paint in the nearby small town and painted the insides, a room 4’ high, 7’ long and about 6’ wide. (Luckily, I lived here only through that summer, and moved into a trailer in the fall!)

On her last day here Swami gave a traditional Indian fire ceremony, during which he talked about seeing each day as a new beginning. Then he gave the Sunday service, which she attended. She was thrilled by these experiences and bought some of Swami’s books to take with her. A few days later I received a letter from her from San Francisco, where she was visiting my sister. She wrote, “I feel like I’m walking along in a column of light, looking at people without any criticism or judgment.” I was amazed at the change in her. Unfortunately, when she returned home and talked with my father, she began to doubt her experience here, and all her original doubts about Ananda surfaced again.

In August of 1971 Swami started the monastery here. On some level the monastic life called to me, but it also frightened me. I had just come onto the spiritual path and didn’t feel ready for another leap at that point. It took a year or two for me to sort out my feelings. Early in 1973 I asked Swami if I could join, and he seemed pleased. As we chatted about other things, I said, “Don’t you want to tell me anything about what I should do as a monastic?” He said, “No…you know what to do.” It was true. Once I opened my mind to it, monastic life was perfectly natural to me. I think I have spent many past lives as a monastic.

In the early days of the monastery, because of the feeling of family here, the monks and nuns felt close to each other like brothers and sisters. Swami called us to his house one evening and said that if we wanted to be monastics, we should not be fraternizing with the opposite sex, even in seemingly innocent ways. We should not look into each other’s eyes, because of the magnetism that comes through the eyes. That meeting was thrilling, and a great aid to our clarity. As we left the room, everyone was being so careful to avoid eye contact with the opposite sex that we were kind of bumping into each other clumsily as we put on our shoes to leave.

After that we said goodbye to any friendships with the opposite sex. We wouldn’t get into any conversations that were personal. We might talk about business but learned not to talk in a way that drew attention to ourselves. It helped me to become more giving in my energy, less asking for attention from someone else. I moved to a trailer in the Ayodhya monastery that was quite cozy inside, with a wood stove. Every morning the nuns would wake at 5:15 a.m., energize under the large oak tree, and meditate in our teepee temple. Then we’d head off to work, many of us working in the Publications business together.

In 1980 Seva asked if I would move to the Seclusion Retreat to be David Praver’s assistant. Our guest program was located there at the time. (In 1983 it moved to its present location and became called The Expanding Light.) I moved to the Seclusion Retreat still a nun. Seva even sent a sister nun, Catherine, to the Retreat as a support for me. But my monasticism was beginning to feel contractive. Up to that point, my years in the monastery had been tremendously strengthening to me. Committing my life to God alone had helped me to become more focused and centered, stronger in my spiritual life. Yet as I examined my heart, I felt that now I needed to be more inclusive of other people’s realities, more loving and accepting of everyone.

Thanksgiving of 1981 I had dinner with Bharat at the Seclusion Retreat. I consciously relaxed my impersonal approach, and we had a warm and interesting conversation. As we talked I felt as if I knew him very well. Inside, I felt a voice saying, “This is your next step in renunciation.” This was a shock to me, but it felt like inner guidance.

On the one hand, I have always felt extremely blessed by that experience and by my marriage to Bharat. And at the same time I’ve found marriage to demand a much deeper level of renunciation in me. When I was a nun, my will power was supreme. Suddenly I found myself with someone who wasn’t following my orders. And, in addition, he had a will of his own. What a shock this was to me in the first years of our marriage! Now my desire to live according to what I think God wants has to be blended with what my husband thinks God wants! It keeps me on my toes, helps me renounce likes and dislikes on a deeper level of my being. It is a great blessing to be with someone who is trying to do the same thing. For each of us God is our first love, and that is what brings joy and harmony to the marriage.

One of the things I noticed about Ananda my first days here was the respect with which people treated each other. Each person is given the space to develop naturally from the inside out. People give each other the space to make their own decisions and let their own integrity guide them. Moving here, I remember feeling almost a tangible sense of increased personal space around me. People don’t give you unsolicited advice, nor do they require deep interpersonal, emotional sharing. I was impressed with a feeling of interpersonal cleanness and freedom.

People here are reluctant to give spiritual advice to others because we realize that people are all different, and what works for me will not necessarily work for another. In this Swami has been the great model. He has watched many people do many stupid things. He lets us make mistakes because he knows it’s the only way people learn, and he trusts that our good intentions and intelligence will bring us around to the truth eventually. If you’ve ever tried to give anyone unasked for advice (and who hasn’t?), you know it simply doesn’t work.

One of the great blessings of living at Ananda has been the opportunity to be with Swami Kriyananda. In my early years I used to be somewhat suspicious of him, always watching him and wondering, “Is he coming from ego?” I had a very doubting nature. At one point he said to me, “Doubt paralyzes you.” That helped me break the doubting habit.

Watching Swami work with people opened my mind to what true friendship is; to love and accept a person completely brings the truest understanding of their nature. I have watched him guide people in such a sensitive and insightful way. Rather than explaining to people what their spiritual blocks were, he would put them in a work situation that would force them to develop the opposite spiritual strength. If a person was dealing with spiritual pride, he might encourage them to take a job that was especially humble, or to work beside someone who expressed true humility.

A few times I asked Swami for guidance about a new direction in my life. He would invariably throw the question back in my lap: “Meditate on this. Ask God what He wants you to do.” He wants us to develop our own intuition, to learn to get our answers from within.

I have heard people complain that Swami is not perfect and that this is some kind of an obstacle. Our biggest obstacle on the spiritual path is ourselves, our own attachment to our limitations and desires. If we can find someone who knows more than we do, who is going to help provide challenges and opportunities for us to grow, I think we should tune into them as deeply as possible. Swami does not see himself as the guru, and has been very clear about this to us. That doesn’t mean that it isn’t helpful to tune into his wisdom, since it is greater than mine.

In my early years here Swami hired me to work for his publications business doing promotions. He suggested a certain direction, and I disagreed with it quite strongly. It’s not as if I were basing my opinion on any experience in the publications business. I was about 26 and hadn’t had much business experience at all. Asha asked me about the situation, and I explained Swami’s idea versus mine, and how, being a writer, he had an egotistical attachment to his own idea. Asha’s next statement was one of the strongest single statements anyone has ever made to me. She said, “Who do you think has more ego? You or Swami?” The implications of this statement exploded in my mind. Swami’s ego was not the key factor here. The big problem I faced was my ego.

I try to tune into Swami’s soul as much as I can in my heart. I try to be open to the flow of God through him. For me it has been a doorway to expanding my consciousness. I also try to do this with other devotees whom I respect spiritually. This doesn’t interfere with the fact that Yogananda is my guru. I try to open myself to Yogananda’s influence to the core of my being. And I feel that the people in my life are sent to me by him: some to test me and to help me grow stronger in non-attachment; others to be spiritual examples.

The guru is very alive in my life, in terms of inner communication. I try to ask inwardly which direction I should take, what I should say to a person who needs help. If I feel a contractive or nervous energy in my heart, that is the wrong direction to go. If my heart feels calm and happy, that is the right direction to go, or the right thing to say. The guru helps us grow toward our own highest potential.

People sometimes ask, “How has Ananda changed since the early years?” On the one hand there is much more physical development and much more organizational structure. But on the human level there is not much change. The people who came in the early years were sincere, humble, devotional, and enthusiastic about serving God. The people who come today are the same. The community has just grown deeper in all of these qualities.

One of the things that strikes me about Ananda is the superconscious approach to life. By this I mean that people, while aware of problems, don’t give too much weight to problems. Instead, we are always seeking solutions, and always assuming solutions exist. In the early days, as I’ve said, there was practically no money. And yet it never occurred to most of us that the place could fail. We’ve always held a positive attitude that we will find the solutions to whatever obstacles face us.

Ananda has its own vibration. Certain people are drawn to live here, others aren’t. When people come to Ananda, their soul is leading them. Otherwise it’s not worth the risk of giving up a high-paying job for an uncertain future in the country. People come with high spiritual aspirations, as well as outer images of community life: lots of friends, a comfortable life in the country. Sometimes when they face loneliness or tremendous obstacles on the physical plane, they feel Ananda has failed them. Their disappointment about not living up to their spiritual aspirations makes them want to blame someone other than themselves.

I’ve found that if people can accept the challenges in their lives and the challenges here, there is an atmosphere that is tremendously helpful to the spiritual life. Spiritual growth is not handed to you on a platter. Most people feel enthusiastic to face challenges on the path, but then when the tests come, we feel, “Not this test. I was thinking of a different test. This one is too hard!”

A friend of mine was sent off to head up one of our city centers. It was torture for her. Her personality didn’t mix well with the people in the center, and she hated the particular city she was in. At one point, she said to Swami, “I don’t think I’m the right person for this center. They need someone more lively and outgoing.” My friend is a very deep, inward person. Swami’s reply was, “I didn’t send you here for them, I sent you here for you. I thought it would help you develop as a person.”

This is the kind of life tests Ananda gives. You think that you are needed to build the work. Then you see the work is here to build you. The more we realize we’re the ones who need to change and grow to adjust to the circumstances of life, then we’re seeing things in the right way.

I feel Ananda is an ocean of sanity, where people respond to life, for the most part, in a healthy fashion. We try to live simply and find joy within. We treat all people with respect and honor the goodness in other people. This environment helps one express the best qualities within oneself: the natural love of the heart, as well as openness, kindness, and trust. In such a nurturing environment people develop deeper faith in themselves and develop their inner strength. I see this in community members, and I see it in guests who come to visit The Expanding Light even for a few days.

True humility is self-forgetfulness, not thinking about your smallness, not thinking about yourself at all. Humility is very personal because it has to do with your relationship with yourself. Are you obsessed with your own thoughts and feelings, or are you trying to discover what God wants? My partnership with God is not a matter of philosophy. It’s a moment by moment experience. Sometimes it takes me aback to feel how close He is, how much He is paying attention to my thoughts and actions. Yogananda used to say, “God is the nearest of the near, the dearest of the dear. Do not keep Him away.”